As most of you know, I spend a good chunk of the month of June in Israel, attending a class on Film Producing. In addition to praying at the Western Wall and standing on top of the hill where Jesus was crucified, I actually did do a lot of film related stuff there as well. Which included seeing some great films from the region.

Case in point:

"The Syrian Bride", from director Eran Riklis, tells the story of a young woman from the Golan Heights who's engaged to be married to a soap opera star in Damascus. The Golan Heights is part of territory that the Israelis seized from Syria during The Six-Day War in 1967, and Syria still considers it part of their country. In fact, the Druze, the ethnic minority who live there, including our bride, also consider themselves Syrian and many of them have refused Israeli citizenship. Her family is hoping she can have a better life in Damascus, and have agreed to this arranged marriage. But, because of the political situation, once she crosses over the border into Syria, she can never come back to Israel to see her family again. So, in many ways, her wedding day is like a living funeral. It's just an incredibly beautiful film that makes the politics of the region deeply personal. I don't know if it has an American distributor yet, which is a real shame. If you manage to catch it on video or at a festival, I highly recommend checking it out.

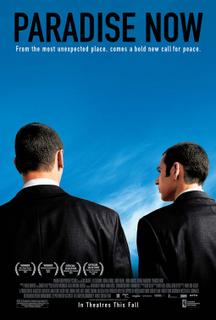

On the opposite end of the spectrum is the intense drama,

Paradise Now. Produced by an Israeli, but directed by a Palestinian, it follows two Palestinian men who volunteer to become suicide bombers. You watch them transform from a pair of shaggy, laid-back auto mechanics, into sleek, focused, living killing devices as they prepare for their last day on this Earth. Then, the plan goes totally wrong and the two of them are actually forced to confront their reasons for volunteering in the first place. Again, an instance where the political is simply a manifestation of the violently personal.

When we screened this film during the class, once of the producers came to speak afterwards. Needless to say, a number of Israeli students gave him a real tongue-lashing for glorifying the suicide bombers. One of the Jewish American students even went so far as to accuse the film of being anti-Semitic because she was unsatisfied with how it depicted the impact of the bombers on Israeli society. In the end, all of his detractors felt that the film was unbalanced.

To which, I say, "of course".

Film is not journalism. It has absolutely NO obligation to be balanced. It's a story, and every story is entitled to it's point of view. Personally, I didn't think the film was particularly anti-Semitic because, quite frankly, you never see the Israelis. The Palestinian characters talk about them like they're an abstraction, in much the way a lot of Black Americans talk about "The White Man". The film had no intention to be balanced - it's a Palestinian story. An unpleasant one, I'll grant you. But, let's be honest - it's not like there is anyone who DOESN'T know the impact of suicide bombers.

I'm much more interested in "why?". Why would someone, another human being, with a family and a job and a life, volunteer to die just so they could kill complete strangers? I suspect that the answers lie in a despair that is so pervasive, that one can begin to feel that they're one of the walking dead.

While I was there, I also caught a free screening of

The French Connection in honor of the director William Freidkin, who was in Tel Aviv directing an opera version of "Samson & Delilah". And, while that particular film is still fairly popcorn, the opportunity to hear Friedkin talk coincided nicely with these two Middle Eastern films. Freidkin told a story about his first film: when he was a young man working for a local TV station in Chicago, he met a priest at a party who worked on Death Row. Friedkin asked the priest if he thought any of those prisoners were actually innocent. When he told him yes, Friedkin grabbed a camera and a cameraman from his station and marched right down to the State Penitentiary. The end result was the TV documentary

"The People vs. Paul Crump". Once that film found it's way into the hands of the Governor of Illinois, Paul Crump was granted a stay of execution.

In Freidkin's words:

"That's when I learned that a film can save a life."

Why am I saying all of this?

I am a filmmaker.

In fact, my first produced feature film could be coming to a theatre near you in 2006. But more about that much, much later.

I love movies, and I've loved them all my life. Perhaps they're why I don't really have a Baltimore accent - because I was spending more time with James Bond and Superman and Indiana Jones and

Herbert West and

Scotty Ferguson and

Mike Church, than with the people across the street. But, I firmly believe that movies matter.

Vertigo matters to me.

Deeply. Emotionally.

Apocalypse Now matters to me.

Spiritually.

American Beauty matters to me.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon matters to me.

Menace II Society matters to me.

Even genre films like

Forbidden Planet and

Star Trek II and

John Carpenter's The Thing or comedies like

50 First Dates or even a deeply flawed movie like

Ali matter to me. They matter in my life.

And they matter not because they're historically accurate or chock full o' facts or a bold indictment of some great wrong.

They matter because they move me. They move me to laugh, or cry, or cheer, or scream, from some place deep inside my heart.

I was asked recently about a film I'd just seen in the theatres, which was #1 at the box office, and I couldn't give it a ringing endorsement. It had it's moments, and the actors were fine and the production was sound.

But, when the credits rolled, the audience simply filed out in silence. No chatter. No applause. Nothing.

In the end, this particular movie simply didn't matter to me. And, I suspect that many of my fellow audience members felt the same way.

The Syrian Bride and

Paradise Now matter to the lives of thousands of people I'll never meet across Israel, who's stories may have never been told.

And they remind me that, when I make films, they must matter. First and foremost, they must move my soul first.

"Well, I've TRIED to be a model citizen, General Lane. I KNOW I promised I wouldn't waste my intellect on Kryptonite robots and elaborate super-death traps. I KNOW that.

"Well, I've TRIED to be a model citizen, General Lane. I KNOW I promised I wouldn't waste my intellect on Kryptonite robots and elaborate super-death traps. I KNOW that.